Industry News

Why Climate Change Will Be A Leading Cause Of Migration In The Next 30 Years

- Posted on Jan 31, 2022

- In Opinion

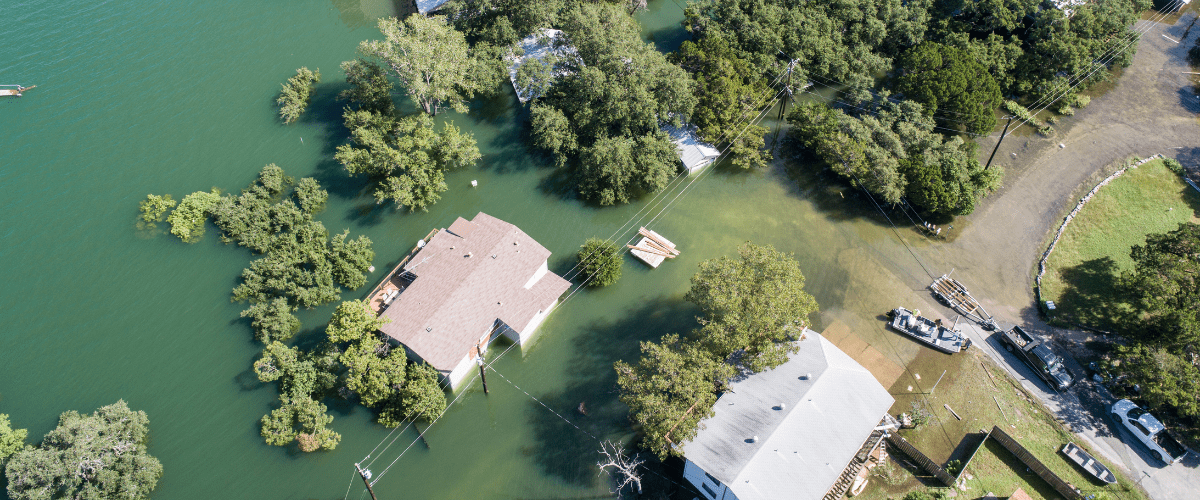

Within the next three decades, hundreds of millions of people could be forced to relocate as climate change intensifies. Who stands to be impacted the most? And how will the global landscape change in the face of mass displacement?

Each year, some 20 million people are already forced from their homes due to natural disasters and uninhabitable environments triggered by climate change. But the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that by 2050, that number will skyrocket to 250 million – more than the current population of Brazil.

The UNHCR has dubbed this new class of displaced people “climate refugees,” essentially those who have been forced to relocate due to environmental factors, as opposed to security or economic issues alone. What’s driving these large-scale migrations? Rising temperatures, desertification, water scarcity and more frequent extreme weather events, such as droughts, wildfires and severe hurricanes.

Environmental or “climate” migration isn’t limited to the developing world, either. While places like Africa and small island nations will be affected disproportionately to the rest of the world, developed and stable countries like the Netherlands and Japan are among the most at risk from rising sea levels and adverse weather incidents.

Asian “megadeltas” – large river deltas that stretch across China, India and Southeast Asia – are also especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change, due to expected decreases in freshwater availability. China is already trying to engineer its way out of this crisis, says Alex de Sherbinin, the associate director at the Center for International Earth Science Information Network at Columbia University, but success is not guaranteed.

“China is going to face a lot of challenges, but they have chosen a very technocratic approach, with major water transfer projects and heavy engineering. It’s unclear if that will build sufficient resilience,” says de Sherbinin. “The main point is that all countries will likely lose out with [climate change], but some may lose less than others.”

With hundreds of millions of people certain to be affected by looming environmental challenges, migration experts are looking ahead, and asking: What might the future global landscape look like as a result?

“The world will have to prepare for increased migration flows. We can already predict where climate refugees will come from – we just don’t know where they’re going to go,” says Armand Arton, president and founder of Arton Capital.

Arton, an expert in global mobility, believes that climate change considerations have already played a role in the adoption of visa-free agreements in the Pacific and Caribbean. Take the island country of Tuvalu as one example. Its passport allows visa-free access to the Schengen Area, and ranks as the 39th most powerful passport in the world as of 23 April 2021, according to Arton Capital’s real-time Passport Index.

“It’s strange for an island with just over 11,000 people, in the middle of the Pacific, to have a strong passport that’s in the top 25 percent globally,” says Arton. “I think the European Commission, and other countries, are giving them this visa-free access for humanitarian reasons. And in that way, some countries endangered by climate change have actually gained a more powerful passport ranking.”

Interestingly, countries that have seen their passports increase in power as a result of these agreements, have also been able to leverage them in the form of citizenship by investment (CBI) programs, which attract much-needed foreign investment. Arton points to examples like Dominica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and Antigua and Barbuda – three Caribbean island nations that benefited from CBI sovereign wealth funds in 2017, after a series of Category 4 and 5 hurricanes (Harvey, Irma and Maria) caused catastrophic damage across the region.

“These countries were able to access funds immediately to provide emergency aid and fix their buildings and roads. If they had waited for aid from the US and Europe, they would still be where they were five years ago – and that powerful economic resilience is funded by CBI programs,” says Arton.

“By creating CBIs, Carribean islands have been able to leverage the commercial power of their passports to generate more wealth for their country and their citizens,” Arton continues. “This in turn has allowed them to tackle issues like outward migration or climate change on their own – and not remain at the mercy of international aid agencies.”

Related news

Is the American Dream really worth living?

2022-10-13Is the American Dream really worth living?

8 out of 10 millionaires in the United States are self-made. That means their

Opinion, United States

This isn’t the time to end the Montenegro CIP

2022-09-14This isn’t the time to end the Montenegro CIP

The Montenegro Citizenship by Investment Program comes to an end on 31st December 2022

Opinion

Limiting the Securing of US Citizenship Through Birth

2020-01-24Limiting the Securing of US Citizenship Through Birth

Opinion piece by Professor J. Craig Barker, on the new US policy aimed at

Opinion

Will Trump make investing in a second passport even more desirable?

2016-11-11Will Trump make investing in a second passport even more desirable?

Americans anxious to join the global citizenship movement Donald Trump’s ascent to the White

Global Citizenship, Opinion